Rome (NEV), 2 April 2018 – “Not only are lives buried in the Mediterranean Sea, but also stories of those who have no grave and of those who cannot be mourned. Other bodies returned by the sea, instead, are buried without a name, with a number often drawn on the limestone”. With these words Francesco Piobbichi, illustrator and operator the Federation of Protestant Churches in Italy (FCEI) for the Mediterranean Hope Refugees and Migrants’ Programme, tells the NEV Agency of the ceremony that took place on 24 March in Badolato, Calabria to commemorate victims of the crossings in the Med.

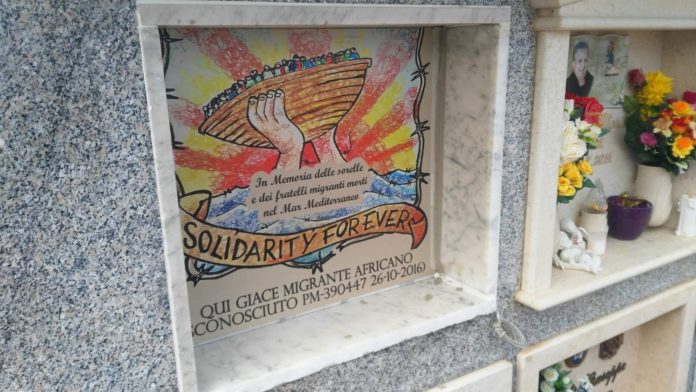

Two plaques of the “Disegni della frontiera” (Drawings from the Border by Piobbichi), were laid during a non-denominational ceremony on the tombs of two African men who died last year in a dramatic shipwreck and were buried in the town’s cemetery. The initiative promoted by the “Terra Madre – Borghi in Comunità” Association, followed a conference on xenofobia organised by the Italian Council for Refugees (CIR) in collaboration with the Municipality of Badolato and the Centre for Asylum seekers and refugees in town. The occasion marked the 20th anniversary of the landing of the Turkish-registered cargo ship, Ararat, which landed at Santa Caterina dello Ionio on 26 December 1997 with 825 Iraqi and Turkish, Egyptian, Lebanese, Afghan and Bengali Kurdish migrants on board.

Two plaques of the “Disegni della frontiera” (Drawings from the Border by Piobbichi), were laid during a non-denominational ceremony on the tombs of two African men who died last year in a dramatic shipwreck and were buried in the town’s cemetery. The initiative promoted by the “Terra Madre – Borghi in Comunità” Association, followed a conference on xenofobia organised by the Italian Council for Refugees (CIR) in collaboration with the Municipality of Badolato and the Centre for Asylum seekers and refugees in town. The occasion marked the 20th anniversary of the landing of the Turkish-registered cargo ship, Ararat, which landed at Santa Caterina dello Ionio on 26 December 1997 with 825 Iraqi and Turkish, Egyptian, Lebanese, Afghan and Bengali Kurdish migrants on board.

“It is not easy to tell the story of the death of the nameless, and it is not easy to transform numbers into history, into memory. Yet, this is one of the main issues I have been working on for years with Mediterranean Hope. Together with the Forum Lampedusa Solidale we have restored the tombstones of migrants who died at sea in the cemetery of the island. I travel all over Italy with my drawings and talk about it. The drawings give me the opportunity to respect the faces, to recount with feeling what occurs in real life. It is not an artistic work, it is not a theatrical performance, but a story that becomes collective and that is told collectively,” explains Piobbichi, who adds, “not only are lives buried in the Mediterranean, but also the stories of those who have no grave, who cannot be mourned. Other bodies returned by the sea instead are buried without a name, with a number often drawn on the limestone. Even though this gesture does not restore the name of these people, it does give them back the dignity they lost at sea. I sincerely thank them, as well as those who have allowed this to happen. These two young men are now part of a collective history, those tombs now represent a gesture of solidarity between human beings and become an indictment against those who transformed the sea that united, into the sea that divides. Transforming numbers into history, and transforming stories into stone, is a hard and necessary job in order to build the memory of tomorrow. My drawings of the border have become exhibitions, books, stories, posters; in short, a collective instrument that allows everyone to take part in the story and to find a frame in which to live as human beings. A frame that is valid for the living and for the dead”.

“It is not easy to tell the story of the death of the nameless, and it is not easy to transform numbers into history, into memory. Yet, this is one of the main issues I have been working on for years with Mediterranean Hope. Together with the Forum Lampedusa Solidale we have restored the tombstones of migrants who died at sea in the cemetery of the island. I travel all over Italy with my drawings and talk about it. The drawings give me the opportunity to respect the faces, to recount with feeling what occurs in real life. It is not an artistic work, it is not a theatrical performance, but a story that becomes collective and that is told collectively,” explains Piobbichi, who adds, “not only are lives buried in the Mediterranean, but also the stories of those who have no grave, who cannot be mourned. Other bodies returned by the sea instead are buried without a name, with a number often drawn on the limestone. Even though this gesture does not restore the name of these people, it does give them back the dignity they lost at sea. I sincerely thank them, as well as those who have allowed this to happen. These two young men are now part of a collective history, those tombs now represent a gesture of solidarity between human beings and become an indictment against those who transformed the sea that united, into the sea that divides. Transforming numbers into history, and transforming stories into stone, is a hard and necessary job in order to build the memory of tomorrow. My drawings of the border have become exhibitions, books, stories, posters; in short, a collective instrument that allows everyone to take part in the story and to find a frame in which to live as human beings. A frame that is valid for the living and for the dead”.

Badolato is a small medieval town in the province of Catanzaro, 5 kilometers from the sea. Its history of welcoming migrants dates back to the 1990s when the town gave hospitality to refugees from the Ararat in the houses located in the old part of the town, which were abandoned in the 1950s after a flood. Badolato is the pioneering municipality of so-called “widespread reception”.